Authors:

Jans Mynbayeva, Research Associate at Ergon Associates

Sam Kelly, Consultant at Ergon Associates

Laura Kazembekova, expert at KAZENERGY Association Human DevelopmentDepartment

A new study of Kazakhstan’s energy companies shows that, although women play a significant role in the energy sector, there is substantial scope to increase the depth and breadth of their participation, particularly in senior management and technical and operational roles. International experience suggests that increasing women’s participation in the sector is vital for meeting current and future workforce needs and can have significant positive impacts on broader business performance.

Kazakhstan’s energy sector is crucial to economic stability and growth, and there is increasing recognition from companies and policymakers that strengthening women’s representation in the workforce is a potential source of competitive advantage, helping to secure the ongoing sustainability of the sector in a rapidly changing global context.

Although the Government of Kazakhstan collects gender-disaggregated national employment data, there are still industry-specific data gaps with respect to women’s participation in management and technical occupations. To expand the knowledge base on women’s employment in Kazakhstan’s energy sector and inform ongoing discussions on increasing female representation in the workforce, KAZENERGY Association and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) conducted a comprehensive study of the role of women in the sector.

The study was developed by Ergon Associates, a London-based consultancy that specialises in gender, employment, labour and human rights and has successfully supported energy companies in emerging markets to strengthen their human resource management frameworks with respect to equal opportunity and to increase the number of women employed in technical and managerial roles.

The KAZENERGY-EBRD study, based on a workforce survey of 36 energy companies operating in Kazakhstan, covers more than 55,000 workers over the period 2016 to 2019. Findings from the study have now been published in a joint KAZENERGY and EBRD report, which also draws on national and international examples of good practice on promoting gender diversity and equal opportunity to set out how companies can better support women’s employment and leadership in the sector.

Key findings on women in the energy sector

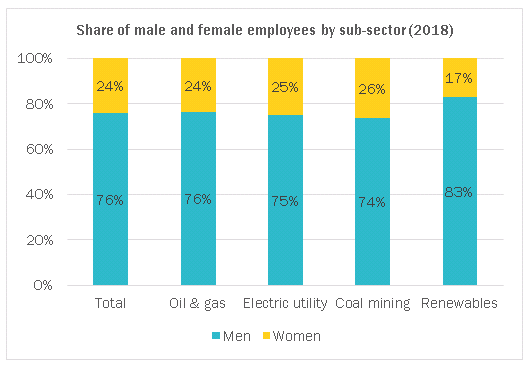

Although Kazakhstan compares favourably to international benchmarks with respect to women’s share of total energy sector employment, the KAZENERGY-EBRD study found that women remain underrepresented in the workforce across all energy sub-sectors, including oil and gas, electric utility, renewables, and coal mining. From 2016 to June 2019, women accounted for approximately 25% of the total energy sector workforce on average, with little indication of significant positive change over the period.

Study data also suggests that energy companies are missing out on female talent in their leadership teams. Across the companies surveyed, women represented just 17% of Board members and 12% of senior management teams. A third of companies had no women on their Boards, while almost half of the companies surveyed had no women in their top management team. These figures emerge in the context of a progressive decline in women’s share of employment from non-management roles (26%), through mid-level management positions (20%), to senior management (12%) and Board level, indicating that women’s leadership potential is underutilised in the sector. Women are particularly under-represented in management roles related to technical and operational business functions, making up just 10% of mid-level managers in technical and operational fields compared to 43% of mid-level managers in business and administration functions.

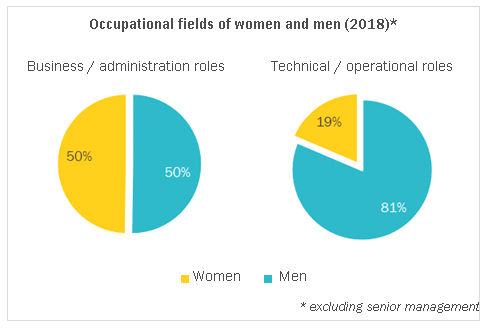

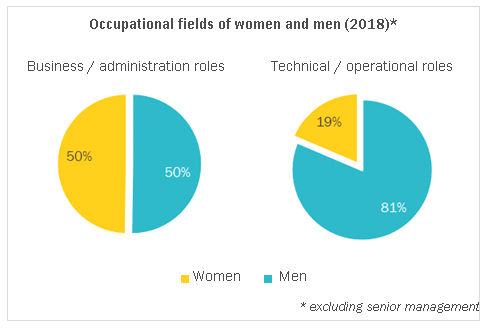

Similar trends in terms of women’s and men’s occupational segregation are identifiable across the workforce. Women account for 50% of all employees (excluding senior management) in business and administration roles, but only 19% of employees in technical and operational roles. Notably, where women do enter technical and operational fields, they do so primarily at higher skill levels; for example, as ‘specialist professionals’ in roles such as production engineers, oil and gas engineers, power engineers and others. However, most jobs in the sector are in the category of ‘other skilled workers’ – non-specialist roles including production equipment operators, machinists, electricians, mechanics – where women’s share of employment is significantly lower (12% compared to 31% of ‘specialist professionals’).

Women’s greater representation in higher skilled technical positions is reflected in a higher level of education for women across the workforce. A total of 64% of women working in the energy sector hold advanced university qualifications, compared to 48% of men. Although these data suggest that Kazakhstan’s energy sector is an attractive employment option for high-skilled women, they also demonstrate that women’s under-representation in senior leadership roles cannot be attributed to an absence of qualified women.

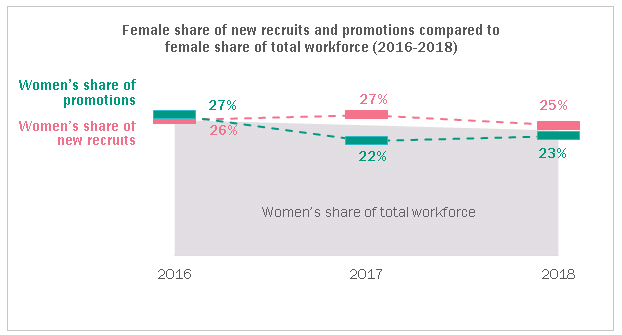

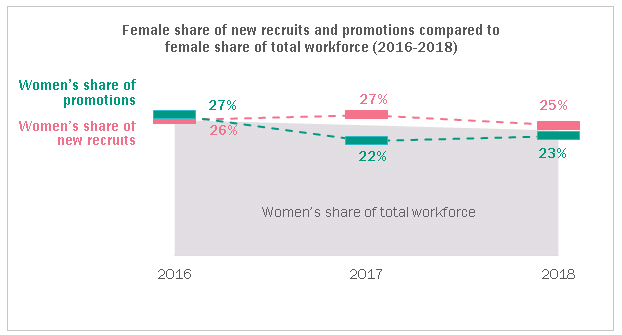

Overall, data from the KAZENERGY-EBRD study do not indicate significant changes in women’s employment in the sector over time, at least in the short term. For example, women’s share of new recruits in the period 2016 to 2019 was broadly consistent with women’s share of the total workforce. Similarly, women’s share of promotions to mid-level and senior management roles fell slightly below the female share of all employees who were potentially eligible for such promotions. These trends indicate little prospect for substantial change in women’s representation across the sector – in management roles and in the workforce overall – without proactive measures to increase women’s employment in energy.

Undoubtedly, there is scope for companies to do more to promote gender equality in the sector. Company initiatives today are mostly focused on public reporting, maternity, and general policies on non-discrimination and equal opportunity. Only a third of the companies surveyed have adopted proactive initiatives to promote equal opportunity beyond statutory requirements. More companies will need to adopt policies and practices that actively promote women’s employment in the sector, including initiatives to increase female participation in technical fields and facilitate talented women’s access to leadership opportunities, if fundamental gender inequalities in the energy sector are to be effectively addressed.

Challenges

Despite growing recognition of the value of widening women’s participation, there remain numerous challenges to achieving gender equality and ensuring equal opportunity in the energy sector. These include ongoing regulatory restrictions on women’s employment, the under-representation of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) studies (particularly in technical and vocational education and training), and challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities. At the same time, negative stereotypes and misperceptions can deter women from pursuing careers in energy or applying for technical positions typically viewed as ‘jobs for men’. Tackling these challenges requires concerted attention from the government, energy sector companies, and other stakeholders.

Meeting the challenge: policymakers

Many governments, including the Government of Kazakhstan, have now adopted policies and programmes aimed at increasing female labour force participation and promoting diversity in public and private sector leadership. For example, expanding women’s involvement in vocational training within high-value and technical sectors and combatting discrimination against women in non-traditional occupations are among the key objectives of the Concept of Family and Gender Policy in the Republic of Kazakhstan to 2030. The Concept also contains targets to increase women’s share of decision-making roles in the executive, representative, and judicial branches of government as well as in the state, quasi-state, and corporate sectors to 30% by 2030.

National policy and legislation are crucial levers for strengthening women’s participation in the energy sector, and the KAZENERGY-EBRD report identifies a number of ways in which Kazakhstan’s policymakers can further support women’s employment and leadership in the energy sector. For instance, the Government of Kazakhstan has already taken positive steps to reduce statutory restrictions on women’s employment, removing 75 occupations from the list in 2018 on the grounds that these occupations were no longer detrimental to women’s health. However, current regulations still prohibit women’s employment in 212 occupations, barring women from highly paid industries such as energy. It is important that policymakers continue to review the requirements and working conditions associated with specific occupations – in consultation with employers – to assess whether more jobs can be removed from the prohibited list. In addition, policymakers could help strengthen women’s representation in the energy sector by working with educational institutions and companies to encourage and enable more women to take up STEM subjects and technical training programmes.

Meeting the challenge: companies

Leading energy sector companies – internationally and in Kazakhstan – are setting out to tackle the under-representation of women as a matter of business priority. Given the scale of the challenge involved, companies often choose to adopt an integrated strategy that targets progress across a range of different areas, and tackles women’s recruitment, retention, and progression. The KAZENERGY-EBRD report profiles the initiatives taken by five diverse energy companies: Karachaganak Petroleum Operating B.V., Samruk-Energy JSC, Tengizchevroil LLP, China National Petroleum Corporation, and KEGOC JSC. For example, some companies have established partnerships with universities, TVET colleges and schools to encourage more young women to pursue careers in the energy sector, whilst others have set up internal women’s networks and mentoring programmes to support the professional development of their female employees. These examples of good practice can provide a valuable template for guiding energy companies’ efforts to attract and retain more women. In several cases, such initiatives reflect the content of specific recommendations for companies set out in the KAZENERGY-EBRD report.

Among other initiatives, the report outlines the following concrete potential steps that companies can take to support women’s employment and leadership:

- Demonstrate public commitment to increasing women’s representation in their own operations and the energy sector more widely. Senior leaders in the industry have a very important role to play in leading change, by speaking out in support of gender equality and being seen to provide personal support for women’s increased participation in the sector.

- Support women’s professional progression and promotion to leadership positions by ensuring that internal promotion and development processes are truly objective and merit-based, and that women have equal access to professional development, mentoring, and training opportunities in order to build the pipeline of female talent.

- Strengthen recruitment and outreach activities to attract more women into the sector. Companies can work with educational institutions to raise awareness of employment opportunities in the sector – for women and men – while ensuring that their recruitment processes and communications promote equal opportunity and counter stereotypes about the ‘unsuitability’ of the sector for women.

- Invest in creating safer and more inclusive working environments that respond to the needs of women and men alike. In order to attract and retain more women, companies should have measures in place to ensure a respectful workplace, including a zero-tolerance environment for discrimination and gender-based violence, and gender-sensitive mechanisms for women workers to lodge grievances and seek support. Companies can also consider how they can introduce policies and practices to support work-life balance for both women and men, including support for care responsibilities.

- Collaborate and share experiences with other companies and industry platforms. Although it is crucial that individual energy companies develop their own policies and strategies on gender equality, companies can achieve much greater impact on women’s representation in the energy sector if they also work collaboratively. For example, KAZENERGY Women Energy Club is an important avenue for collaboration amongst energy companies in Kazakhstan, and can provide opportunities for sharing examples of good practice, coordinate policy dialogue with all stakeholders on issues related to women’s education and employment, and promote women’s participation in the sector. One of the solutions within the framework of the KAZENERGY Women Energy Club could also be the creation of an information-sharing platform to exchange experience on supporting gender initiatives.

Results of the EBRD/KAZENERGY study highlight that widening female participation in Kazakhstan’s energy sector requires proactive action. As such, it is necessary for policymakers and companies to work together to identify effective measures to promote women’s entry and progression in the sector, in order to realise the social, economic, and business gains from increased gender diversity.

The full KAZENERGY-EBRD report will be available at

www.kazenergy.com.

‘Specialist professionals’ refers to employees who typically engage in activities related to the implementation of complex technical and/or practical tasks that require in-depth theoretical knowledge, expertise, and technical skills in a specialised field (aligns with occupational categories ‘2XXX - Specialists / professionals’ of the official Classification of Occupations, 2017). Examples include production engineers, oil and gas engineers, chemical engineers, electrical engineers, etc.

‘Specialist professionals’ refers to employees who typically engage in activities related to the implementation of complex technical and/or practical tasks that require in-depth theoretical knowledge, expertise, and technical skills in a specialised field (aligns with occupational categories ‘2XXX - Specialists / professionals’ of the official Classification of Occupations, 2017). Examples include production engineers, oil and gas engineers, chemical engineers, electrical engineers, etc.

‘Other skilled workers’ refers to employees who are not specialists but typically hold some form of qualification / certification that is required to carry out job tasks in standard conditions and with a certain degree of independence (aligns with occupational categories ‘7XXX - workers in industry, construction, transport, and related fields', or ‘8XXX - operators of production equipment, assemblers, drivers' of the official Classification of Occupations). Examples include workers responsible for the routine operation of technical installations, machinists (e.g., of a flushing unit or mobile compressor), electricians responsible for basic repair of equipment at oil depots, mechanics carrying out routine maintenance of technical installations, etc.